|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

|

|

Ten years ago, officials at the Wallingford Country Club watched helplessly as portions of the golf course began to

lose their distinctive New England feel, a longtime selling point for the 110-year-old, member-owned business.

Purple loosestrife, an invasive plant that can grow up to 10 feet tall, began overtaking wet areas of the 18-hole

course. "You couldn't see the cattails," said Scott Gennings, the golf course superintendent.

Although Gennings couldn't put a dollar figure on the real or aesthetic losses, he said some of the club's 300

members, whose annual fees range from $1,000 to $8,000, began complaining that the course was losing its appeal.

Using herbicides was out of the question. "We're too close to the stream," said General Manager David Timek. And

renting heavy equipment to dig up the roots was too expensive.

They were stumped: "There was nothing we could do," Gennings said.

It took a fourth-grader to come up with an inexpensive solution.

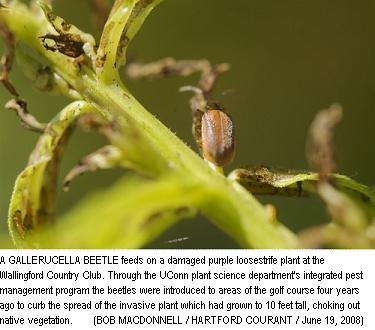

In 2003, Gennings' then 9-year-old daughter, Megan, told her father that she was raising Galerucella beetles and that

the European import's favorite pastime was ? guess what! ? munching on the roots, stalks and leaves of purple loosestrife.

The following spring, Gennings released about 1,500 of the tiny beetles, which he obtained free through a University

of Connecticut program, into the club's wetlands.

Today, he's a die-hard beetle fan.

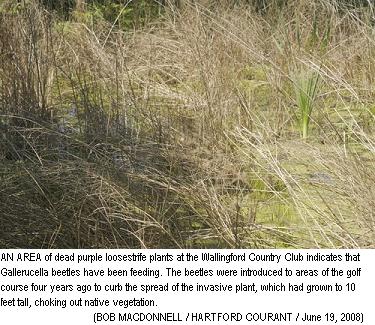

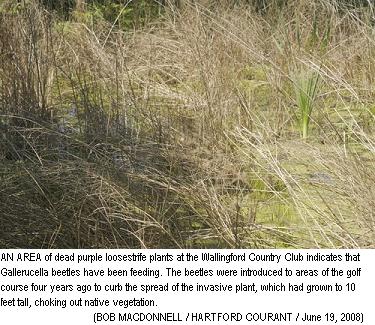

"They do great things," Gennings said as he walked across a wetland littered with dead and dying stalks of

loosestrife.

"It's unbelievable. It's really stunted now. It's thinner. It looks unhealthy. The native plants are coming

back."

With the loosestrife in retreat, club members have noticed that the greens look more like a "New England-style golf

course," Timek said.

"It would have required a backhoe to dig this stuff out," he said. "That, alone, would have been very costly, along

with the damage done to the surrounding greens. We're working with a tight budget in a tight economy.

"Scott is very ingenious. He was able to handle the problem without a lot of expense."

Imported from Europe in the 1800s as a garden ornamental, loosestrife, sometimes known as the "beautiful killer," is a

standout in any crowd. During the summer the perennial, which is banned from sale in Connecticut, adorns itself in a mantle

of gaudy purple flowers.

"The problem with purple loosestrife is the public loves it. It's a beautiful plant," said Bob Heffernan, executive

director of the Connecticut Nursery and Landscape Association. "When it's in bloom, people will run into the garden store

and say they want some or they'll dig it up and move it to their garden, which is illegal."

But its good looks belie its destructive nature.

Each year, public and private entities spend an estimated $45 million in an attempt to control loosestrife, which not

only damages wetlands but is threatening agricultural crops, according to the federal Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force.

In some areas, loosestrife's thick, woody stems, which can grow up to a half-inch in diameter, have blocked irrigation

channels, threatening farmlands, pasturelands and crops.

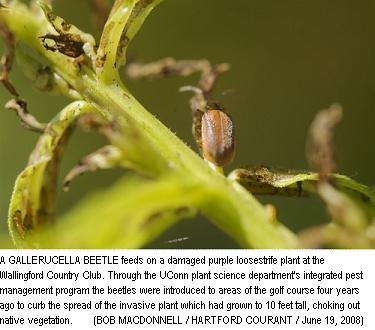

In 1992, the Galerucella beetle was approved as a biological control for loosestrife by the U.S. Department of

Agriculture. Four years later, federal and state authorities approved its introduction to Connecticut.

Now it's hoped that the insect will succeed where man, machetes, earthmovers and chemicals have failed and that it

will eliminate 80 percent of loosestrife over the next 10 to 20 years without harming the environment.

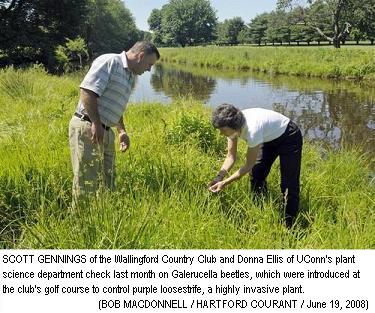

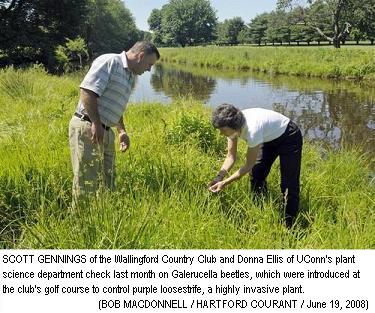

On a recent afternoon, Gennings was giving Donna Ellis, an extension educator with the University of Connecticut's

plant science department, a tour of the club's wetlands, where the native plants ? rushes, tussock sedges, milkweed and

goldenrod ? were flourishing, providing food and habitat to birds, muskrat and monarch butterflies.

Clad in boots to ward off ticks, Ellis had to search the rushes closely to locate a runty, leaf-eaten patch of

loosestrife.

"They look skeletonized," Ellis said, joyfully.

Clinging to their motley leaves were the tiny beetles and their mustard-colored larvae.

"I can't believe it," she said to Gennings. "When I first came here, all you could see was the loosestrife."

Each spring, Ellis teaches the care and rearing of the beetles at a series of free public workshops, funded by the

university and an $8,500 grant from the federal agriculture department.

Since 2004, she's introduced landscapers, groundskeepers and others to the brown and black beetles, which are raised

on pots of loosestrife. Six mating pairs can produce 1,500 offspring in six weeks.

Since 1996, more than 1.4 million of the beetles, which overwinter underground, have been released at more than 100

wetlands throughout the state. The beetles are typically kept in check by predators, including lady beetles, stink bugs,

spiders and birds, Ellis said.

Although the Wallingford Country Club saw improvement in four years, not all the beetle-release sites have experienced

such dramatic results, Ellis said.

In some areas of the state, including a major birding area in South Windsor, flooding has curtailed the beetles'

population. There it may take 10 or more years to see results, Ellis said.

The Wallingford club isn't the only golf course to have successfully deployed the beetles. Sable Oaks Golf Club, a

public course in South Portland, Maine, has used them, as have several golf courses in New York, said Jim Skorulski, a

senior agronomist with the United States Golf Association.

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

|

|

Copyright 2008, The Hartford Courant

Contact Janice Podsada at jpodsada@courant.com.